PDF available here.

Executive Summary

The U.S. Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system is failing to meet the demands of modern great-power competition.It was built for the Cold War’s priorities: controlling proliferation and limiting Soviet access to American technology. But U.S. priorities have changed. America needs a FMS system that enables strategic collaboration with partners, meets today’s fast-moving threats, and adapts to ever-changing technology. While adversaries like China with fewer restrictions deliver arms rapidly, the U.S. is bogged down by red tape, leaving allies vulnerable and undermining deterrence.

Key Problems:

- Cold War Legacy Systems: The FMS system was built to control proliferation, not to enable strategic collaboration. Today’s defense landscape demands rapid integration with allies, particularly in software-driven and commercially developed technologies.

- One-Size-Fits-All Approach: Trusted allies like Israel, Japan, and Poland endure the same review delays as less U.S. aligned countries, straining partnerships and damaging readiness.

- Regulatory Overload: The defense procurement process is governed by tens of thousands of pages of regulations (FAR, DFARS, service-specific policies), stifling innovation and discouraging new market entrants.

- Stalled Innovation: Unpredictable timelines and politically driven reversals deter private sector investment, especially among small and mid-sized innovators critical to future capability.

- Global Competition: China and Russia are delivering weapons faster and more flexibly, gaining influence in key regions. Iran and North Korea are also growing as arms suppliers to authoritarian allies and proxies.

Core Recommendations:

Build a Trusted Partners List

- Create a formal list of vetted allies eligible for expedited contracting, reduced oversight, and prioritized delivery.

Establish a Defense Surplus Transfer Authority for Trusted Partners

- Establish a Defense Surplus Transfer Authority to quickly provide trusted allies with decommissioned but capable U.S. military platforms instead of letting them rot in storage.

Empower a Central Arms Sales Leader

- Establish an Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Cooperation to unify FMS decisions and oversight across DoD, State, and the NSC.

Streamline Technology Security Reviews

- Replace linear reviews with parallel processes and firm deadlines (e.g., 60 days), eliminate outdated offices like the Defense Technology Security Administration, and sunset duplicative boards like the National Disclosure Policy Committee.

Hold Contractors Accountable

- Enforce existing penalties in the Federal Acquisition Regulation for missed delivery timelines due to internal delays. Reduce dependency on large primes.

Open the Door to Innovator

- Reduce regulatory and cost barriers for small and nontraditional firms. Allow rapid inclusion of off-the-shelf and commercial-origin systems.

Incentivize Production Ahead of Demand

- Use advanced procurement and long-lead investments to stabilize manufacturing and preserve skilled labor. Predictability drives expansion.

Expand the Special Defense Acquisition Fund (SDAF)

- Fund export stockpiles in advance. Consider a Defense Export Loan Guarantee to support U.S. industry fulfilling allied orders.

Create a Congressional Commission on FMS Reform

- Modeled on the Cyberspace Solarium Commission, empower an expert panel to review authorities, propose statutory changes, and eliminate inefficiencies.

Rewrite the Arms Export Control Act (AECA)

- Modernize export laws to prioritize agility and collaboration with trusted partners. Legislation like the SPEED Act offers a starting blueprint.

Redefine Controlled Technologies

- Categorize systems based on security sensitivity—e.g., legacy platforms, software-defined systems, and dual-use commercial technologies—enabling low-risk exports to move faster.

Replace Case-by-Case Micromanagement with Strategic Oversight

- Allow broader Congressional notification thresholds and reduce political second-guessing for pre-cleared systems sold to vetted partners.

Reform the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)

- ITAR is a major barrier to innovation and allied collaboration. Expand exemptions like those granted under AUKUS to other trusted partners. Simplify licensing and eliminate “ITAR taint” that deters co-development.

Modernize Arms Cooperation and Procurement Processes

- Adopt time-based export models: pre-approve systems, negotiate pricing in advance, and stockpile inventory for faster delivery.

- Reform procurement staffing and IT infrastructure to prioritize professional, not political, leadership.

Create Pre-Negotiated Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) Contracts

- IDIQ contracts for trusted partners would include fixed pricing, modular configurations, and fast production options, giving allies and industry greater predictability.

Revive a Strategic Export Pre-Clearance Group

- Reestablish a group like the former Arms Transfer and Technology Release Senior Steering Group (ATTR-SSG) to proactively determine exportability by partner and system—removing bottlenecks before they occur.

Introduction

America’s Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system is broken. It was built for the Cold War and sought to control proliferation and limit Soviet access to American technology, not to enable strategic collaboration with partners and not built for today’s fast-moving threats and rapidly developing technology. The process is painfully slow, deterring American allies’ defense investment in American aircraft, firepower, technology and electronics, and defense systems, weakening U.S. credibility abroad. Our allies want U.S. weapons, but antiquated rules and bureaucratic delays keep them waiting years.

The consequences are dangerous. China’s defense exports now dominate in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia, and are rapidly gaining ground in Central Asia and the Middle East. Russia is simultaneously arming Hezbollah with advanced anti-tank missiles while cutting deals with North Korea to refill its own artillery and rocket stockpiles—fueling terror abroad even as it builds up its military industrial base for war.

Reforming the FMS system is a national security imperative. Cutting red tape will diversify America’s defense industrial base and client base, a boon for American companies and homeland security. Reforming the FMS system can spark a new wave of economic reinvestment in America’s industrial base by allies abroad and the American private sector. By cutting unnecessary red tape and signaling to investors and tech companies that defense innovation is a national priority, we open the door to new factories, supply chains, and jobs—particularly in the Rust Belt and manufacturing-heavy regions.

According to the Aerospace Industries Association’s 2024 report, the U.S. aerospace and defense sector exported $135.9 billion in 2023 and supported 2.21 million American jobs. On average, every $1 million in end-use sales supports about four jobs—translating to roughly 4,000 jobs per $1 billion in exports. Accordingly, FY2023’s $238 billion in FMS deals approved support nearly one million U.S. jobs. FMS reform that accelerates and expands the execution of deals could create and sustain hundreds of thousands more jobs—many in regions of our nation hit hardest by industrial decline.

A more efficient FMS process gives companies the confidence to expand production, hire skilled workers, and build up the infrastructure needed to meet global demand. FMS reform isn’t just about helping allies; it’s about rebuilding the American economy. The Trump Administration should lead FMS reform in the spirit of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), embracing lean, agile solutions that empower trusted officials, eliminate duplication, and accelerate decision-making. It’s about cutting the bad, keeping the good, and restoring competence to the heart of American defense exports.

Arsenal of Red Tape: How America’s Bureaucracy Is Failing

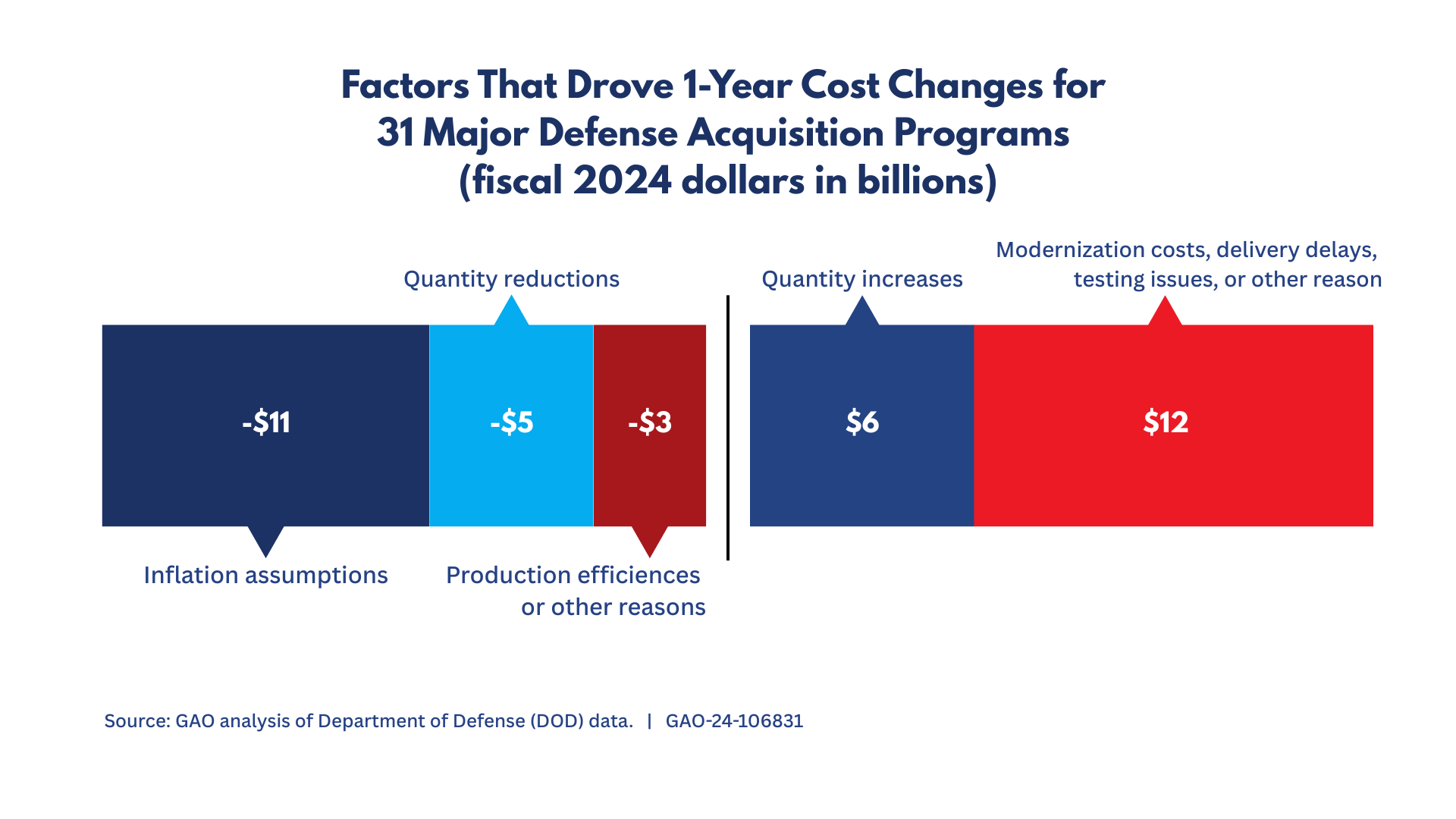

- It takes years to deliver key systems. On average, it now takes 11 years—from initial concept to final delivery—for a major defense acquisition program to reach completion. While China moves five to six times faster and spends far less to achieve comparable capabilities, the United States FMS system is stuck in a procurement model that rewards complexity over speed. These are not isolated problems, they’re symptoms of a broken process that leaves allies vulnerable and adversaries emboldened.

- It’s stuck in a Cold War mindset. The FMS system was built in an era when the United States dominated nuclear, aerospace, and telecom innovation, and its primary goal was to keep cutting-edge technology out of Soviet hands. But today’s battlefield is defined by rapidly evolving, software-informed systems and a globalized innovation ecosystem. Defense breakthroughs now come as often from commercial firms and allied partners as from U.S. labs, yet our export controls remain rooted in a 1970s framework (The Arms Export Control Act) designed to prevent proliferation, not enable collaboration. Bureaucratic hurdles like the Technology Security & Foreign Disclosure (TSFD) process, where multiple agencies conduct sequential reviews, can take months to approve even routine systems. This slow, linear model was never designed for fast-moving digital warfare. As a result, outdated laws and legacy processes are crippling America’s ability to share, iterate, and integrate with our most capable partners at the speed modern deterrence demands. That must change.

- It treats allies and adversaries the same. The current system treats close friends and non-aligned nations the same way, failing to distinguish between trusted democratic partners and countries with less strategic alignment. This one-size-fits-all approach forces our most reliable allies—such as NATO members, Indo-Pacific partners like Japan and Australia, or Middle Eastern security partners like Israel and the UAE—to endure the same sluggish review processes as countries with histories of instability, weak governance, or inconsistent defense cooperation with the United States. By not differentiating between high-trust partners and lower-tier recipients, the FMS system wastes precious time, burdens critical relationships, and undermines deterrence where it matters most. We should adopt a system that fast-tracks weapons sales to close allies and partners. That means creating a trusted partner list with clear criteria and privileges, ensuring close allied countries aren’t stuck in line behind less reliable actors.

- Requirements creep. One of the most persistent causes of delay in the FMS process is the sheer weight of outdated and excessive regulation governing defense procurement. The Department of Defense (DoD) and the Defense Industrial Base (DIB) are forced to navigate a labyrinth of statutes, regulations, and internal policies that stifle speed and innovation. As was highlighted in a recent House Oversight Committee hearing on Defense Innovation, the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), the cornerstone of federal procurement, spans over 2,000 pages. This is further compounded by the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), which adds another 3,000+ pages. On top of these, each military service—Army, Navy, Air Force—maintains its own acquisition supplements, guides, and manuals, generating thousands more pages of requirements that contractors must comply with. This regulatory overload creates a system optimized for bureaucracy, not speed. It discourages new entrants, slows delivery timelines, and weakens America’s ability to compete with faster-moving adversaries like China. Reforming this overgrown thicket of red tape is essential if we are to build a modern FMS system fit for great power competition.

- It stifles innovation. Companies can’t ramp up production when foreign sales are plagued by unpredictable timelines, opaque review processes, and politically driven reversals. When it can take years to get approvals—and even longer to finalize contracts and deliveries—private firms are reluctant to invest in new production lines, hire skilled labor, or expand manufacturing capacity. This uncertainty deters capital investment, especially from small and mid-sized innovators who can’t afford to wait out multi-year government delays. It also discourages foreign partners from co-developing or co-producing systems in the United States, weakening the competitiveness of our defense industrial base and limiting job creation in the American heartland. Without confidence that FMS demand will be met with timely decisions, the private sector holds back—and innovation stalls.

In a world of great-power competition, we must equip our allies faster than our enemies outmaneuver them. But with 25,000 people working in the FMS pipeline process across multiple agencies, from start to finish, and a bureaucratic morass, our system is collapsing under its own weight. Taiwan’s delays are a glaring case in point. Deliveries of critical systems to Taiwan like F-16V fighter jets, TOW-2B missiles, and Paladin howitzers - collectively worth over $20 billion - have faced delays. In one case, Joint Standoff Weapons approved for sale in 2017 didn’t get a production contract until 2024.

Other allies have faced dangerous hold-ups too. Poland’s request for additional HIMARS and integrated air defenses has faced more than 18 months of delays despite frontline urgency. Saudi Arabia and the UAE saw deliveries of precision munitions and drones delayed by 2–3 years due to political reviews. The Philippines’ attack helicopter order has been on hold for over a year, caught in Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) cost disputes and interagency confusion, jeopardizing deterrence in the South China Sea.

The Arsenal of Autocracy: A Comparison

Meanwhile, China is a growing force in the global arms trade, rapidly expanding its footprint by offering fast, affordable, and politically unencumbered weapons to a widening network of clients. While its global share remains smaller than that of the U.S., Russia, or France, China is closing the gap—especially in regions like South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Pakistan remains its top recipient, with a steady stream of JF-17 fighter jets, frigates, and drones, but China has also made inroads with countries like Nigeria, Algeria, Thailand, and the UAE through sales of VT-4 tanks, Wing Loong drones, and air defense systems.

These exports are often delivered faster and with fewer strings attached than Western alternatives, allowing China to buy influence and strategic access at low cost. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China exported major arms to 44 countries in 2020-2024 and, unlike the United States, avoided the massive case backlog typical of the FMS system. Instead, Beijing emphasized faster, one-off deliveries drawn from existing inventory over complex, multiyear government-to-government pipelines.

Meanwhile, although Russia’s share of the global arms market has shrunk since its invasion of Ukraine, the destination of its exports has shifted into more dangerous hands, enabling rogue actors across the globe. According to SIPRI, while Russia’s global arms export footprint shrank by 64% between 2015–2019 and 2020–2024, Russia focused heavily on fulfilling existing deals and demonstrated far fewer delivery backlogs compared to the U.S., with many agreements already completed. Additionally, Russia is producing about three million artillery shells a year. That’s about three times more than the West.

Both Iran and North Korea are emerging as exporters themselves—sending drones, missiles, and artillery to proxy groups and authoritarian allies, often in coordination with Moscow and Beijing. America’s competitors are not just arming themselves, they’re building an alternative arms network designed to undermine the U.S.-led security order.

We want China and Russia reacting to American tech around the world—not the other way around. But that requires speed, agility, and trust in our foreign military sales. America hasn’t had a revolutionary export since stealth aircraft like the F-117 Nighthawk. We’re overdue for bold moves.

Policy Solutions: Recommendations for Reform

- Build a Formal “Trusted Partners List” with Defined Benefits. The U.S. must create a formal “Trusted Partners List” that grants specific benefits to pre-qualified allies and partners, further divided into Tier One and Tier Two level partners. These should include streamlined approvals, expedited contracting, prioritized delivery, and reduced oversight for low-risk transfers. Criteria for inclusion should be based on shared strategic interests, existing defense agreements, and demonstrated compliance with end-use monitoring. This tiered approach would ensure our most capable partners are treated as such—enhancing deterrence, strengthening interoperability, and reducing uncertainty across the board. Streamlining allied defense cooperation requires removing outdated red tape, such as exempting close partners from burdensome congressional notification requirements and eliminating duplicative Third Party Transfer approvals. These changes would accelerate joint defense production and strengthen coordination with trusted partners. This list should be formalized by statute or executive order, with periodic review and the ability to add or remove countries based on performance and strategic shifts. Tier One partners should include NATO and AUKUS countries as well as key regional partners like Taiwan and Israel, while Tier Two partners could include emerging partners such as India, the Philippines, and Gulf allies. Furthering America’s commitment to building closer relationships with its emerging allies, the U.S. should also work with its Tier Two partners to establish a roadmap for reaching Tier One status after several years.

- Establish a Defense Surplus Transfer Authority for Trusted Partners. The U.S. should create a formal Defense Surplus Transfer Authority to enable the rapid transfer of decommissioned but still-capable U.S. military platforms to trusted allies, rather than sending them to storage or scrap. Many systems retired from U.S. service—such as aircraft, vehicles, or munitions—remain highly effective for partners facing asymmetric or high-threat environments. Yet these platforms are often discarded despite their proven performance and strategic relevance. This new authority would allow the Department of Defense to pre-clear select systems for expedited transfer to countries on the “Trusted Partners List,” bypassing bureaucratic delays and leveraging equipment the U.S. no longer needs to strengthen allied deterrence. Instead of discarding capable, upgraded platforms, the U.S. should prioritize transferring them to trusted allies who can put them to immediate operational use. For example, rather than sending upgraded A-10s to rot in the boneyard at Davis Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, the U.S. could transfer them to an ally like Taiwan—where they would bolster defenses against maritime invasion and drone swarms at minimal cost. By empowering allies with proven American platforms, the U.S. can close capability gaps, reduce delivery backlogs, and reinforce deterrence without waiting a decade for new systems to come online.

- Empower an Arms Sales Leader. No single office or leader within the Department of Defense is fully empowered to coordinate international arms cooperation. This has led to stovepiped decisions, misaligned priorities, and delays that frustrate both allies and industry. Congress should authorize the creation of a new Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Cooperation, reporting directly to the Deputy Secretary of Defense. This office should oversee all aspects of FMS, co-production, and technology transfer, ensuring unified leadership and faster decisions across the interagency, including with counterparts at the Department of State, Congress and the National Security Council.

- Streamline Tech Security Reviews. Technology security reviews—especially those involving legacy processes like the Technology Security & Foreign Disclosure (TSFD) system—remain some of the worst bottlenecks in the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) pipeline. While the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) nominally manages FMS execution, it must coordinate with multiple overlapping offices that lack clear timelines or authority. A single system may be reviewed by TSFD, the Defense Technology Security Administration (DTSA), military service disclosure offices (such as the Secretary of the Air Force for International Affairs [SAF/IA]), the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (OUSD-P), and the National Disclosure Policy Committee (NDPC)—all before reaching the Department of State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) for parallel review under the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR). These reviews often duplicate each other, especially in low-risk cases, and happen sequentially rather than in parallel—delaying decisions by months. This linear process is incompatible with today’s software-enabled, fast-evolving systems. Congress and the Department of Defense should eliminate outdated offices like DTSA, consolidate redundant disclosure functions, and restructure TSFD into a centralized, empowered body. The NDPC should sunset in favor of a streamlined, executive-led review mechanism. Most critically, the process must include firm review deadlines—such as a 60-day cap for non-sensitive cases—and shift to concurrent interagency reviews. Without reform, the United States will remain bogged down by Cold War-era red tape, unable to deliver timely support to allies.

- Hold Contractors Accountable. Defense contractors must clearly communicate production capacity and delivery timelines. If they fail to meet obligations due to factors within their control, they should face penalties—ranging from fines to temporary suspension from FMS eligibility. These authorities exist under the Federal Acquisition Regulation and should be strengthened for foreign sales. Accountability only works when the government fosters real competition, not dependency on a few primes.

- Open the Door to Innovators. Smaller and nontraditional firms must be empowered to compete in the FMS process. That means fewer regulatory hurdles and more opportunities to export promising, off-budget systems. Giving allies access to cutting-edge capabilities strengthens deterrence and reduces reliance on outdated platforms. We need fewer paper barriers and more battlefield-ready solutions.

- Incentivize Production. Let U.S. manufacturers build in advance for anticipated FMS demand. That means supporting advance procurement and long-lead investments to ensure production doesn’t lag behind demand. It’s not just about securing supply, but about unleashing private sector confidence. When defense companies know orders are coming, they invest in new plants, hire skilled workers, and strengthen supply chains. This creates jobs, boosts readiness, and helps retain technical experts whose skills are otherwise lost during production lulls. The current stop-start system makes it difficult to maintain specialized expertise—but stable, predictable demand would fix that.

- Expand the SDAF. The Special Defense Acquisition Fund (SDAF) is a revolving fund used by the Secretary of Defense to finance the procurement of defense articles and services in anticipation of future transfers. It enables the delivery of selected items to partners in less than the normal procurement lead-time. The fund is intended to preserve U.S. force readiness by reducing the need to divert assets meant for U.S. forces in order to meet urgent partner requirements. Congress should expand SDAF and consider establishing a Defense Export Loan Guarantee mechanism—reviving Title 10 authorities to back U.S. production for foreign deliveries. These tools would support the creation of a permanent arms export stockpile and reduce delivery timelines by years.

- Establish a Congressional Commission on FMS Reform. Congress should create a bipartisan, independent commission, modeled on the successful Cyberspace Solarium Commission, to conduct a comprehensive review of the FMS system. This paid commission should have a mandate to examine the full scope of FMS policy, authorities, and bureaucracy, and to develop actionable recommendations for structural reform. It should be empowered to assess and adjudicate interagency roles, identify duplicative or outdated offices, and propose statutory updates, including potential consolidation or elimination of entities. An effort of this magnitude requires sustained, expert attention beyond what agencies can provide alone.

- Rewrite the Arms Export Control Act for Modern Competition: Congress should undertake a full rewrite of the Arms Export Control Act (AECA) to replace its Cold War-era foundation with a framework tailored for today’s great power competition. The existing law was designed to prevent proliferation during a time of U.S. technological dominance; it is ill-suited for a world where innovation is decentralized and threats evolve rapidly. A modern AECA should enable faster collaboration with allies, agile export processes, and a competitive edge in the global arms marketplace. As part of this broader effort, legislation such as the SPEED Act–introduced by Chairman Mike Rogers (R-AL) and Ranking Member Adam Smith (D-WA)–illustrates one approach aimed at modernizing America’s defense acquisition system, which would also include reforms to the FMS process by emphasizing speed, clarity, and strategic focus.

- Redefine Controlled Technologies to Enable Speed: A reformed AECA must include revised definitions of controlled technologies, clearly distinguishing between: legacy platforms with established security risks, software-defined and rapidly updatable systems, and dual-use commercial items. This distinction would allow for faster export of non-sensitive systems, reduce unnecessary controls, and prevent emerging tech from being bottlenecked under outdated classifications. Flexibility must be built in to keep pace with rapid technological change.

- Replace Case-by-Case Micromanagement with Strategic Oversight: Rather than managing arms transfers through granular case-by-case approvals, Congress should adopt modern oversight mechanisms that rely on broader, strategic reporting and notification thresholds. This would preserve accountability while granting the Executive Branch the operational flexibility to meet defense cooperation demands in real time. Systems approved for trusted partners should not be delayed due to excessive micromanagement or political second-guessing.

- Reform International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) to Encourage Co-Development with Trusted Allies: ITARs are one of the biggest barriers to innovation and allied industrial cooperation. Foreign partners often avoid joint programs with U.S. firms due to fear of “ITAR taint”—where any involvement from a U.S. entity permanently subjects a system to U.S. control. AUKUS sets a modest but meaningful precedent, carving out targeted ITAR exemptions that acknowledge the deeper trust and shared security interests we have with real allies. Congress should create ITAR exemptions for our most trusted allies (beyond AUKUS), or implement simplified licensing for approved co-production projects. Allied scientists and engineers should be free to collaborate with their U.S. counterparts without triggering downstream restrictions. These reforms would enable common standards for modular, export-tailored systems and allow partners to build sovereign capabilities while staying interoperable with the U.S.

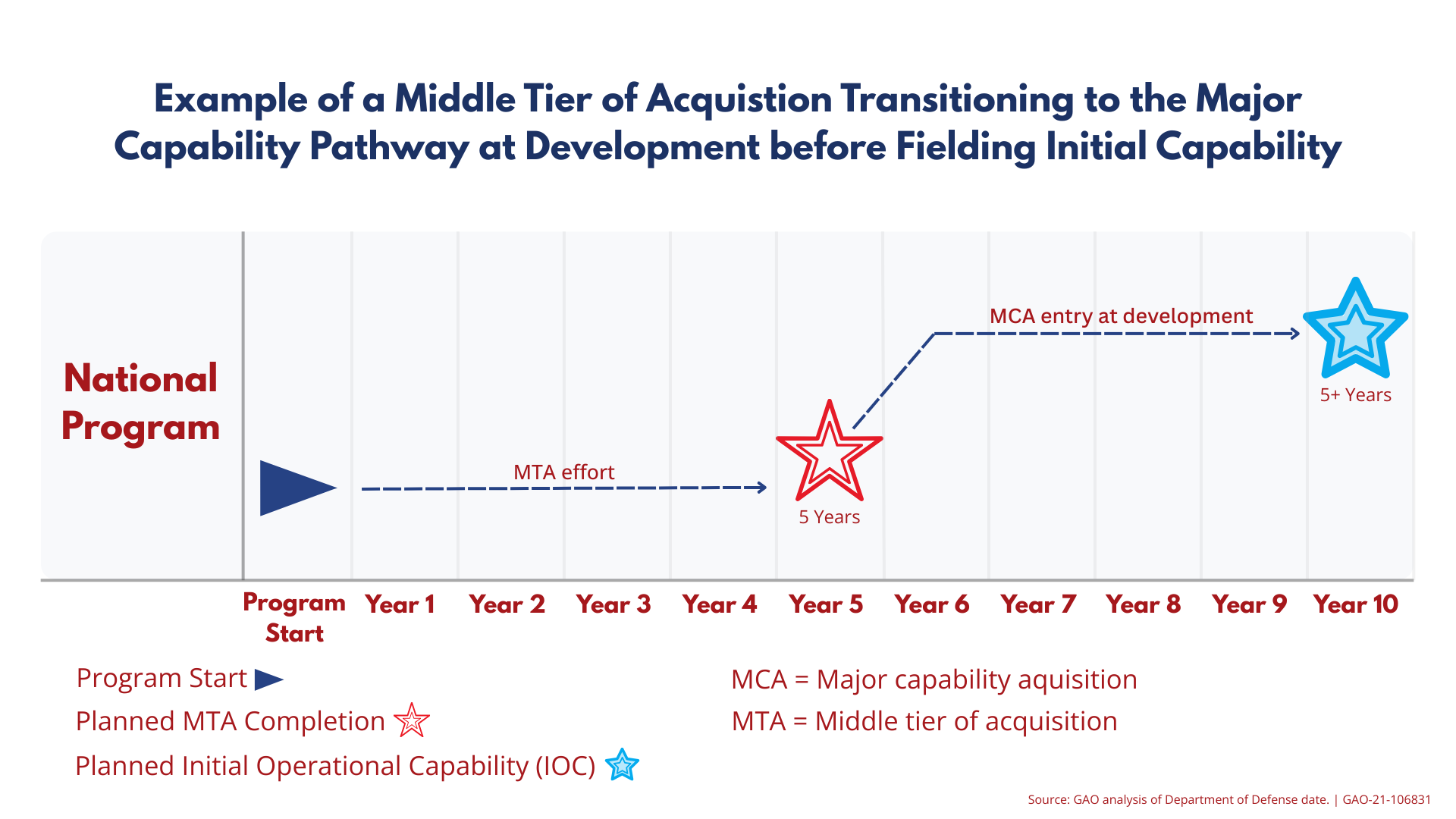

- Modernize Arms Cooperation, Overhaul the Review Process, and Reform Procurement: Export decisions for close allies are too often delayed not by malice, but by the absence of pre-established pathways, antiquated processes, and institutional inertia. The U.S. still relies on a linear acquisition model—pairing outdated requirements with outdated technology—ill-suited for today’s fast-paced threat environment. Legacy IT systems and bureaucratic sprawl compound these challenges, making even routine transfers sluggish and unpredictable. To break this cycle, the U.S. should adopt a time-based arms cooperation model. This means pre-approving certain systems and technologies for export, negotiating prices up front, and maintaining stockpiles for rapid delivery—modeled on successful pathways like Rapid Acquisition and Middle Tier Acquisition already in use within the DoD. This must be coupled with a focused, comprehensive review process that streamlines compliance while preserving oversight. Crucially, procurement reform is needed—not only to cut red tape, but to ensure that experienced acquisition professionals, not political appointees or non-procurement officials, are managing this process. Modernizing IT infrastructure and empowering expert personnel are just as important as policy changes. Trusted allies should not have to wait years for critical equipment simply because our system is stuck in the past.

- Create Pre-Negotiated IDIQ Contracts for Trusted Partners: To provide greater predictability and speed, the Department of Defense should create Indefinite Delivery/Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract vehicles for pre-approved systems bound for trusted allies. These contracts would include fixed pricing, modular configurations, and rapid production timelines, allowing allies to plan defense budgets with confidence while giving U.S. industry the stability to invest in manufacturing and scale. This approach aligns with how the U.S. already manages urgent domestic defense needs.

- Revive ATTR-SSG or a Successor Body for Export Pre-Clearance: The DoD should revive and empower a body like the defunct Arms Transfer and Technology Release Senior Steering Group (ATTR-SSG) to proactively assess and authorize exports by country and capability. This group would make strategic, forward-leaning determinations on which allies can receive which systems—eliminating the need for repetitive, reactive reviews. With a mandate to coordinate across the interagency and a clear timeline for decisions, this mechanism would bring predictability and coherence to the FMS process.

Conclusion

FMS reform isn’t just about selling weapons. It’s about projecting strength, securing our allies, revitalizing our industrial base, and outpacing our adversaries. The Trump Administration and Congress must be prepared to eliminate red tape. That means slashing delays, reforming laws, and getting serious about national security. America must become the Arsenal of Democracy again—not the Arsenal of Bureaucracy.

Further Reading & Congressional Testimonies:

- https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/hearings/to-receive-testimony-on-the-department-of-defense-responsibilities-related-to-foreign-military-sales-system-and-international-armaments-cooperation

- https://oversight.house.gov/hearing/clearing-the-path-reforming-procurement-to-accelerate-defense-innovation/

- https://blog.joelonsdale.com/p/america-needs-better-defense-acquisition

- https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2631-1.html